We're in a renaissance period for brain research that deepens our understanding of how to live a better life. Additionally, modern life calls us to strengthen our awareness and resist the influence of those who use this knowledge to shape how we think, buy, and act.

Of particular interest is how this research informs an aspect of our experience, habit.

What are habits?

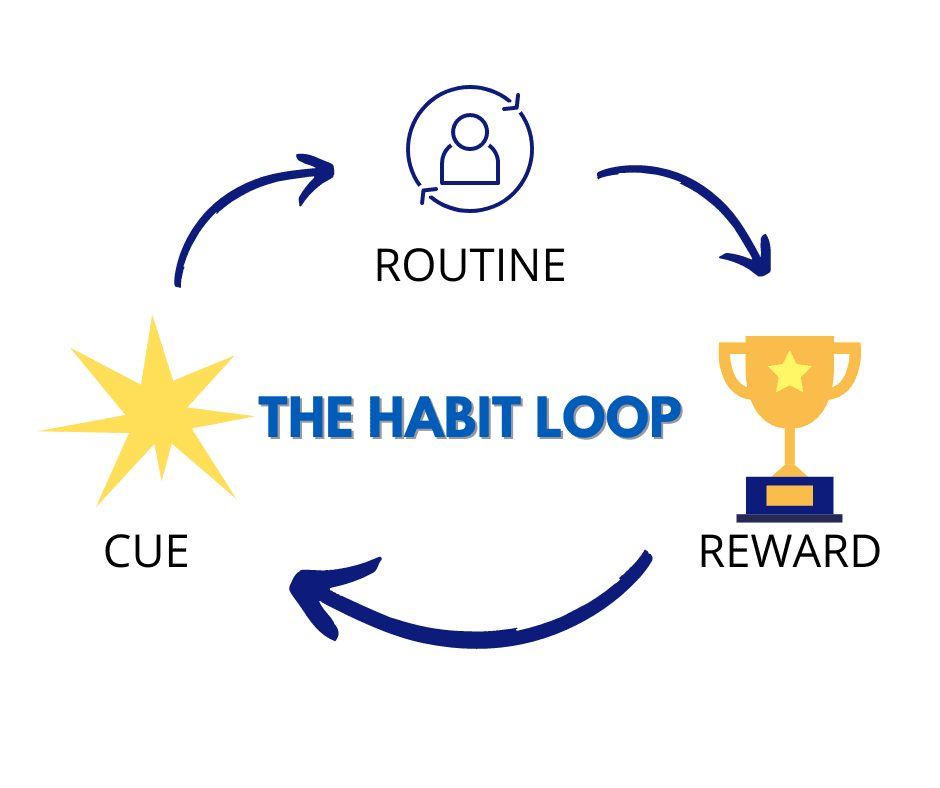

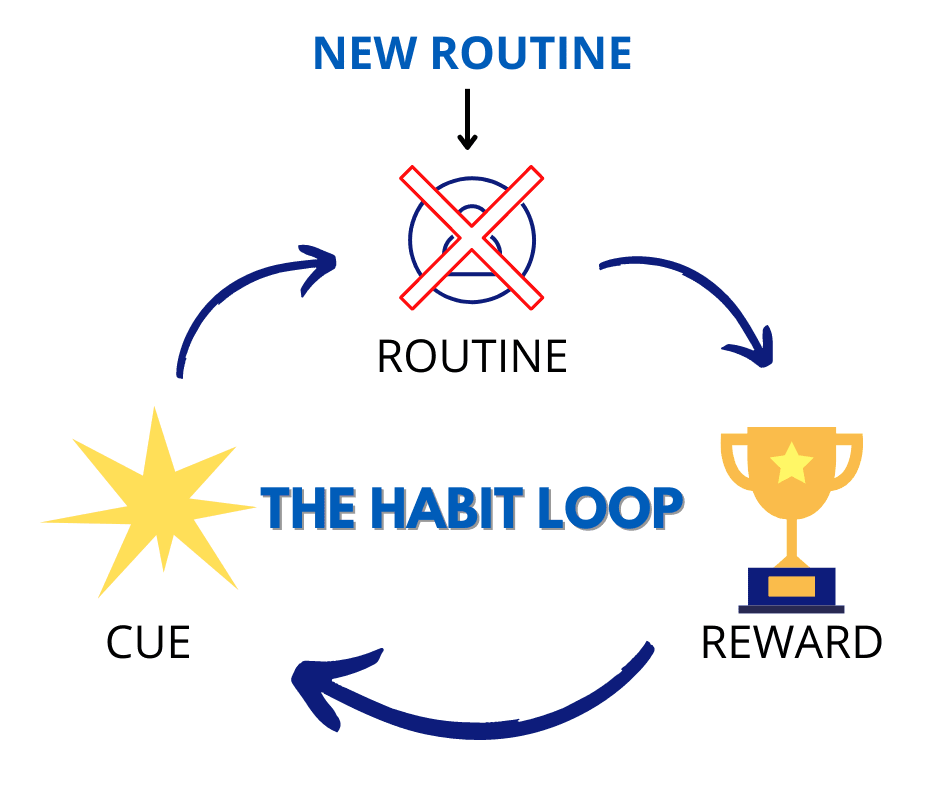

Habit is anything we do repeatedly based on a cue - routine - reward loop. Habits support who we want to be and where we want to go, and habits can stand in the way of how we want to change.

Every habit forms through repetition; generally, our existing habits have served our minds in some way at some point in time.

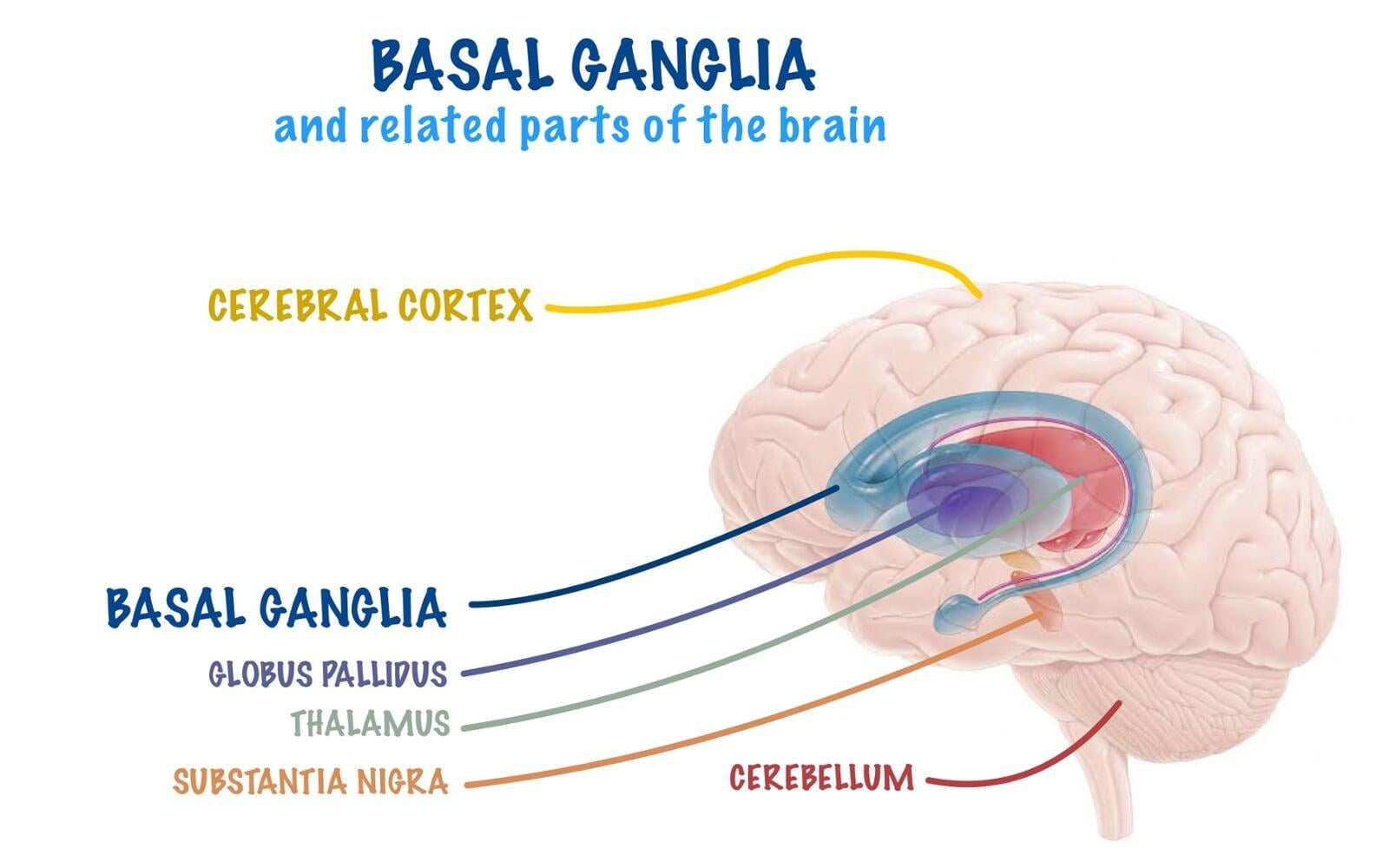

Our procedural memory supports habits and it correlates with functions in our Basal Ganglia. Procedural memory is our back seat driver; unless we consciously intervene, it is happy to take control. It's not part of our conscious process but fills the critical role of helping us master activities.

Procedural memory augments our conscious process with routines that free our mind from thinking through repetitive tasks. Procedural memory uses less energy to complete a task, so the brain defaults to procedural memory whenever possible. The brain conserves energy whenever possible; it's wired that way. Our brain uses about 20% of our body's energy. If it were to use twice that, it would be unlikely early humans could have consumed enough calories to dominate the planet.

An example of procedural routines is driving a car; when you were learning, it required a lot of mental energy. As you mastered the process, it required far less effort. When things change, like driving in a new city, more conscious effort and energy are needed until new routines form in your procedural memory.

The Basal Ganglia communicate with our motor system and the Limbic System, our emotional center. They respond faster to an event than our executive function in the frontal lobe. Many of us have experienced occasions where we reacted to danger but don't remember the instance of reaction - that was most likely the Basal Ganglia in action.

It could also be a habit that is the cue for another habit - for instance, when I talk with people about doing yoga practice at home, I suggest a cue that will support the habit of a home yoga practice. The cue is seeing the yoga mat; I suggest placing it where it will catch their eye and draw them into the routine. The bridge habit is to commit to getting on that mat every day. When triggered by the cue (seeing the mat), they do the routine (getting on the mat). When they build the bridge habit of getting on the mat, it becomes the cue to the more difficult habit of doing yoga.

The Basal Ganglia are connected to our emotional and reward systems; yes, there is a physical structure in the brain that gives us good feelings as rewards. And every habit has a reward; it may be feeling good or relief from feeling bad. The reward can be numbness because that is better than feeling bad.

When creating new habits it's important to be clear on the cue, routine, and reward, so that you consistently practice it the same way. And always celebrate success, thus amplifying the reward.

Changing habits

A method for change is to maintain the cue and the reward while interrupting the old routine and replacing it with a new one. The key to this is clarity on each step in the habit loop; spending time understanding the cue, routine, and reward is critical.

To replace the "routine" in the cue - routine - reward loop.

First, observe yourself in this habit and decide what the components are. Say you discover the "cue" is the feeling of exhaustion after getting the kids into bed, the "routine" is watching TV, and the reward is resting your conscious brain (not having to think), which you get from watching TV. Great, so what other routines would align better with the longer-term goals that would give you the same, similar, or better reward? Maybe doing some massage with your significant other? Maybe getting on the floor for some unstructured gentle stretching, or going for a walk?

Once you've decided on a new routine, you start programming your procedural memory through repetition and make it as easy as possible to do the new routine instead of the habitual one. In this case, perhaps you clear a space on the floor before putting the kids to bed, put out a yoga mat, or check in with your significant other so that you're both ready for your massage exchange. The tendency will be to follow the cue with the old routine until it is interrupted by the new routine.

It's also valuable to add friction, such as unplugging the TV so that you have to take an unusual action to watch it or putting it in the garage while you change the habit. Friction slows things down, adds to the routine, and cues us to make conscious choices.

As you improve at changing habits you can also disrupt a habit at the cue. When I fight with my wife, I tend to feel alone and unloved; that's the cue. I want something sweet to shift the feeling of emptiness, and getting that sweet thing is the routine. This has been one of my most embedded habits as it began in early childhood, so I've dealt with it at multiple levels.

Friction: I don't keep my go-to sweets in the house, so I have to jump in the car and go to the store. By adding friction and a trip to the store, I've expanded the routine, slowed things down, and created a more significant time delay to the reward. Because the trip to the store is not as deeply embedded into the routine, it makes the routine more conscious.

Cue: When the cue happened (fight) I didn't start by changing the reaction of seeking a treat, I would jump in the car seeking a treat, but I gradually turned that into a drive to a park and going for a walk. Then it shifted to a walk or a bike ride. The bike ride gave me a better reward than the treat.

Getting to the root: Often deeply embedded habits were formed in early childhood, under emotional or traumatic experiences. An immature brain created them with limited understanding, resources, or autonomy. Most intractable habits have deep roots and can be hard to transform without changing the mental constructs that support them. Upending an early childhood habit can take years of therapeutic work with different methods and habit change techniques.

Creating New Habits:

I suggest working on at least two complementary habits at the same time. Working on multiple habits is more effective than a habit in isolation because habits are always part of an ecosystem that helps them resist change.

Pick the main habit you want to create. Spend some time thinking about it and get super clear. Spend some time writing about it and make a concise and accurate description. It should be simple, clear, and easy for someone else to understand. Next, write about how you will reward yourself when you do the action; something small that marks your success could be as simple as looking in the mirror and thanking yourself for following through. It can even be something you already do, but you convert to a reward, for instance, your morning coffee. You don't have to get it perfect immediately; this is a process of learning and exploring.

When the main habit is clear, write about what other habit would support the first habit's success. Go through the same process of describing it clearly and concisely.

Here's an example of how habits support each other. Say you want to get more exercise, your main habit could be; Jog 30 minutes every morning. Your supporting habit could be; Get up 45 minutes earlier than usual. Getting up early enough to jog supports the jogging habit and the jogging habit supports the habit of getting up 45 minutes early by helping you sleep better. That way, they support each other.

Adding cues and support:

Get a paper wall calendar and put it in the best place to remind you of your new habits as often as possible.

Mark the day you will start on your calendar; that should be tomorrow unless there is a compelling reason to delay. Any delay will weaken your resolve.

I like to commit to working on a habit for seven weeks. Habits take a while to groove in, and that works for most. So I mark the date on the calendar seven weeks out and write on that day how you will celebrate your success, something significant that acknowledges seven weeks of commitment and action.

Every day you do the routine, mark it on your calendar. Don't require perfection; set your goal of only missing seven days during the seven-week sprint. Giving yourself some leeway makes it easier to start right back up if you miss a day.

As the procedural memory gets programmed, your new habit will become easier.

*A habit generally takes from 18 to 254 days to solidify, depending on complexity, supporting environment, and your ability to build habits.

A few other tips:

Partnering with someone to report to each day, could be a text or email, is a powerful practice. This invites transparency and self-accountability and is most potent if the agreement is to read the text or email and respond, with something like "Thank You". If the response is criticism, comparison, comment, or sometimes even encouragement, it can muddy the process and become a reason not to practice the habit. Even better if they are working on a habit also.

Notice how you respond to every aspect of habit creation; notice your energy levels and enthusiasm. They will inform you of any blocks that get in the way of your new habit.

Realize this is hard work. Generally, we deny it, but we all have difficulty creating or changing habits. Habits can be very complex; in creating new habits, we often go against old, deeply rooted habits that are part of an ecosystem.

When you enter the habit change process, you will start noticing other habits that may detract from your success; these habits may need to be intentionally worked with if they get in the way.

Be honest with yourself, and avoid rationalization. It's easy to fudge but that undermines the process, the implicit memory is very literal and doesn't deal well with ambiguity.

Avoid seeking perfection but cultivate consistency and tenacity. Allowing imperfection reduces the tendency to rationalize. Consistency is required, not perfection.

Continuing through failure builds strength; when you miss a day, start back up tomorrow.

*Phillippa Lally conducted a study in 2009 on habit formation, and the results showed that it takes from 18 to 254 days to create a new habit.